The disappearing language of joy around the hijab

When modesty is framed only as endurance.

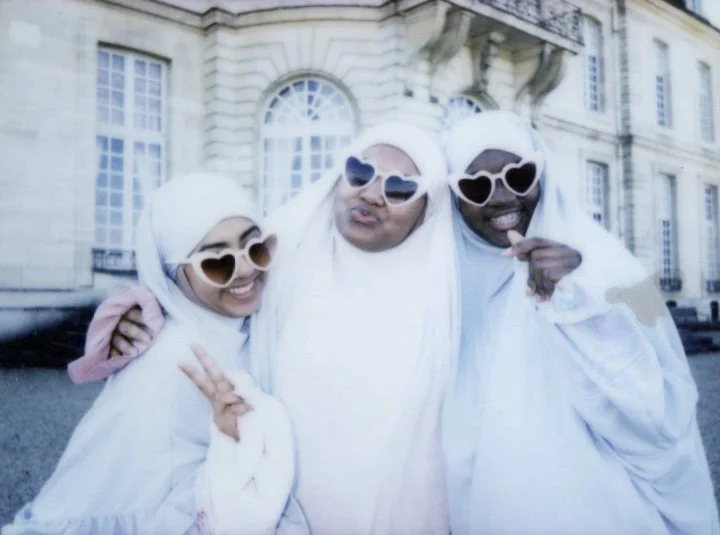

© Les Sultanas

A recurring narrative has emerged across social media: hijab is often described as “hard.” While this is true in the sense that any act of devotion in Islam will encounter trials, the discourse increasingly emphasizes hardship at the expense of joy. This reflection is not about spiritual reward, but about the experiential pleasure, presence, and delight that can accompany wearing the hijab.

What does “hard” really mean?

What does it mean to call hijab “hard”? Often, the term is shorthand for external pressures: racism, Islamophobia, systemic discrimination or even physical danger. Yet it has also come to signify a perceived loss of identity and self-expression. Modesty and hijab, originally prescribed as forms of protection, empowerment and adornment, risk being reduced to endurance alone. The language of joy, the quiet, sustaining pleasure of devotion, the embodied poise of modesty and feminine expression, has begun to fade from the conversation.

Endurance as identity

When modesty is framed solely as endurance, women who wear the hijab are implicitly cast as suffering individuals. Even well-intentioned admiration, whether from Muslims or non-Muslims, can reinforce this perception, echoing societal narratives that view hijab through a lens of oppression. Strength becomes the defining feature of hijab, overshadowing choice, delight and devotion.

The consequences extend beyond perception. In societies like France, where the hijab is restricted in schools and public debate questions its presence for minors, public discourse often positions women as victims in need of liberation. Endurance is no longer merely personal; it becomes a social expectation, shaping both how others see hijabis and how women perceive themselves.

Over time, this narrowing of language can obscure the fuller spectrum of experience. Affirmations of resilience, especially from those outside the faith, may unintentionally reduce hijab to hardship alone, leaving little space for the nuanced realities of joy, poise, embodied confidence and aesthetic freedom. Women may internalize this discourse, forgetting that modesty can coexist with pleasure and the subtle empowerment embedded in daily practice.

Normalized modesty: joy beyond struggle

In many contexts, wearing the hijab is woven into daily life so seamlessly that it is rarely questioned or framed as a challenge. It is part of attire, of routine, of cultural rhythm. In these spaces, modesty functions as a language of self-possession: it shapes posture, gestures and interactions, offering subtle pleasures of embodiment and harmony.

These effects extend beyond the purely visual or ritual. Observationally, women who adopt hijab often experience freedom from certain societal pressures: less emphasis on heavy makeup, less compulsion to conform to rigid beauty standards, and a reduced focus on body modification. Issues like body dysmorphia, compulsive dieting or cosmetic surgery pressures, while not absent, are often less pronounced. Hijab provides a protective cultural and personal framework, enabling women to inhabit their bodies with calm, grace and confidence.

Viewed from the outside, however, these lived realities are often misread. Social media amplifies a narrow narrative of struggle and endurance, presenting hijabis as either constantly succeeding or constantly suffering. In reality, experiences are far more heterogeneous. By attending to these quieter, beneficial dimensions, we reclaim a fuller understanding of what hijab can afford, balancing hardship with subtle but profound rewards.

Acknowledging hardship without losing joy

The contrast becomes clear when this lived experience is viewed from outside. Observers unfamiliar with the faith often interpret modesty solely through the lens of struggle, inadvertently turning what is natural into a narrative of endurance. By ignoring the everyday pleasures, the tactile satisfaction of choice, the self-possession that comes from embodiment and the harmony between faith and form, this discourse risks flattening hijab into a symbol of hardship alone. Recognizing these quieter dimensions restores balance: strength and joy coexist, as do devotion and delight.

This reflection is not a denial of hardship. Racism, danger and social barriers are real, particularly in societies where visibility is met with hostility. Yet a full understanding of hijab must include the language of joy: the serenity of adoration, the poise that comes from self-possession, the solidarity of sisterhood and the aesthetic freedom of modest expression. Endurance and delight coexist; they are inseparable facets of the same practice.

Restoring the language of joy

What might it mean if the language of joy were restored alongside the language of struggle? Younger generations, particularly those encountering hijab for the first time in social media culture, are increasingly exposed to the narrative of suffering. While many experiences are valid, they do not encompass the whole story. Hijab, like womanhood in general, follows seasons: not every day is sunlit, yet the year is incomplete without moments of warmth and light.

Strength and resilience need not eclipse pleasure and poise. In attending to the full spectrum, the quiet joys alongside the trials, we can reclaim a language of hijab that honors both devotion and delight, endurance and celebration.